When a Kid Falls Into the Ape Pit Funny

Without his parents noticing, a 4-year-old boy crawled under a railing, over wires and through a moat to reach Harambe, a 17-year-old Western lowland gorilla at the Cincinnati Zoo, who was shot dead shortly after.

According to reports, just before he fell almost 20 feet into the enclosure, the boy told his mother he wanted to enter it.

"The little boy himself had already been talking about wanting to go in, get in the water, and his mother is like, 'No you're not, no you're not,'" a witness told CNN. "Her attention was drawn away for seconds, maybe a minute, and then he was up and in before you knew it."

Because they believed the boy was in danger, zoo officials killed Harambe. While many disagree about whether or not Harambe was a threat to the child, the zoo officials stand by their decision. But in the aftermath, Harambe's death has sparked debate about who is to blame - the parents? The child? The zoo? Harambe himself?

Many of these questions have no certain answer. But one might ask a more basic question: How and why it is possible for such a small child to even get into an enclosure with a 450-pound animal?

The Dodo ask an expert what one might think would be a simpler version of the question: Why do people sometimes end up in enclosures with zoo animals? The answer delves into the sad and fascinating history of animals in captivity.

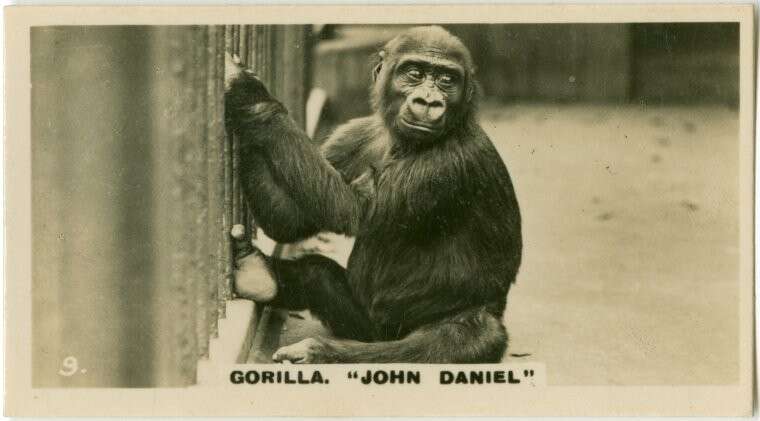

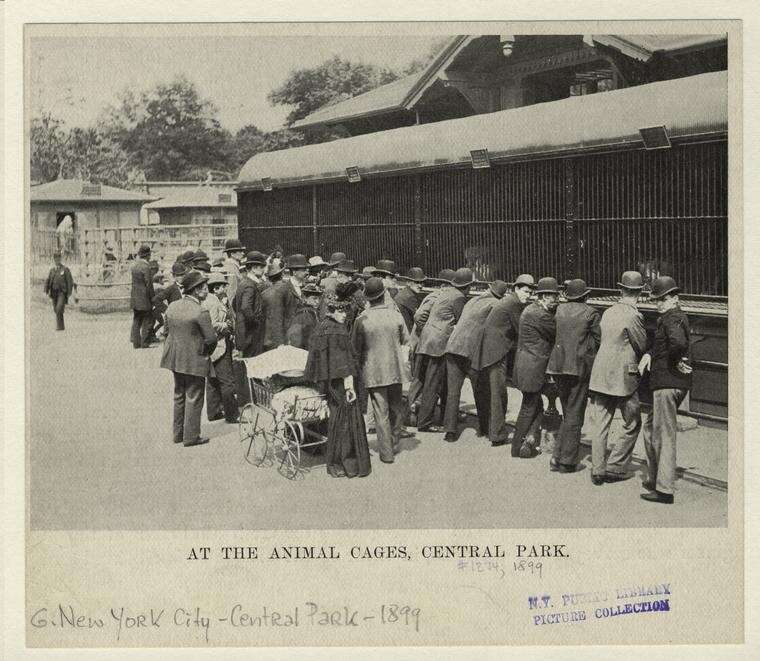

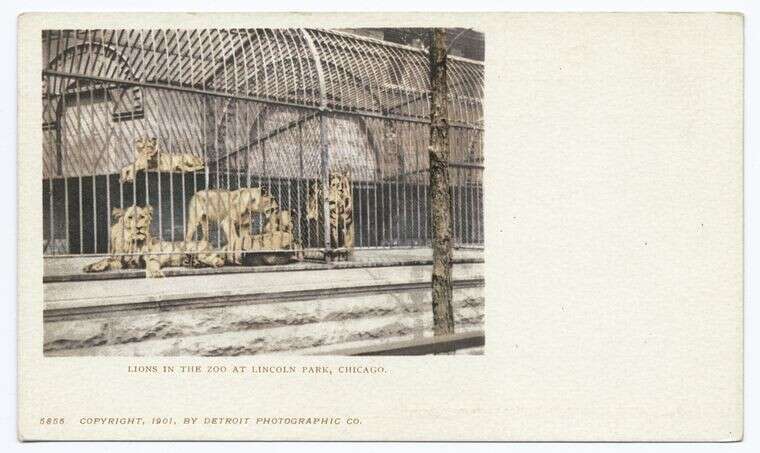

"If we look back 40 or 50 years, you'd go to zoos and see animals behind bars. You'd see them in a way that they're imprisoned, truly imprisoned, which means they're protected and people are protected," Ron L. Kagan, executive director and chief executive officer of The Detroit Zoo, a leading institution for animal welfare, told The Dodo.

As zoos learned more about what animals actually need, Kagan said, things began to change. Zoos opted for more natural, immersive exhibits that would help the animal live more like they would in the wild. But that involved compromises.

Kagan fears that the backlash from the Harambe incident could cause zoos to move backward in their treatment of animals in their hard-won naturalistic enclosures. Kagan pointed out that the "naturalistic and immersive" exhibit at the Cincinnati Zoo has been open for about 30 years.

"If you take into account over a million visitors per year, that incident is horrible but still a rare one," he said.

Even the best designs for animal enclosures often can't guarantee everyone's safety when there's a will to get inside. "When there's an intention to go into an enclosure, it's almost impossible to prevent that," Kagan said. He cited a number of examples of suicide attempts, most recently in Chile, where a man threw himself into a lion's enclosure, forcing zookeepers to kill two lions.

Thriving, not just surviving

The Detroit Zoo was the first major zoo in the U.S. to decide on ethical grounds to no longer keep elephants at all. The Dodo asked Kagan whether he could see this happening for other animals, like great apes, in the future.

"All of us are on this journey to continuously improve things, whether that's conservation or welfare, and thinking of what we could do better for the animals and the public," Kagan said. "What was a big discussion for elephants is now a discussion for cetaceans ... Great apes obviously have complicated needs and it's up to us to provide for those needs, to make sure the animals can behave in a natural way and have a lot of control and choice in their daily lives."

The great apes at The Detroit Zoo live in a 4-acre habitat that is home to two Western lowland gorillas, as well as chimpanzees and drill monkeys. The primates spend their days foraging, grooming and playing, just as they would in their native African environment, according to the zoo's website. Sometimes visitors can't even see the animals because the lush, large area gives them room for privacy when they need it.

"The challenge is for them to thrive," Kagan said. "So, if they're not thriving here, they should go live somewhere else."

He added that one thing is for sure when it comes to issues of animal captivity and conservation: "It's a constantly changing thing. There will be changes."

In the case of Harambe's death, Kagan said, in his view, a human - whether it was the child or the adult - "just made a mistake."

Update: In November, a federal inspection of the zoo found that the barrier (which has since been replaced) was not in compliance with standards for keeping primates in captivity when the boy managed to get in Harambe's habitat. The investigation is ongoing.

Source: https://www.thedodo.com/harambe-zoo-enclosure-history-1836314359.html

0 Response to "When a Kid Falls Into the Ape Pit Funny"

Postar um comentário